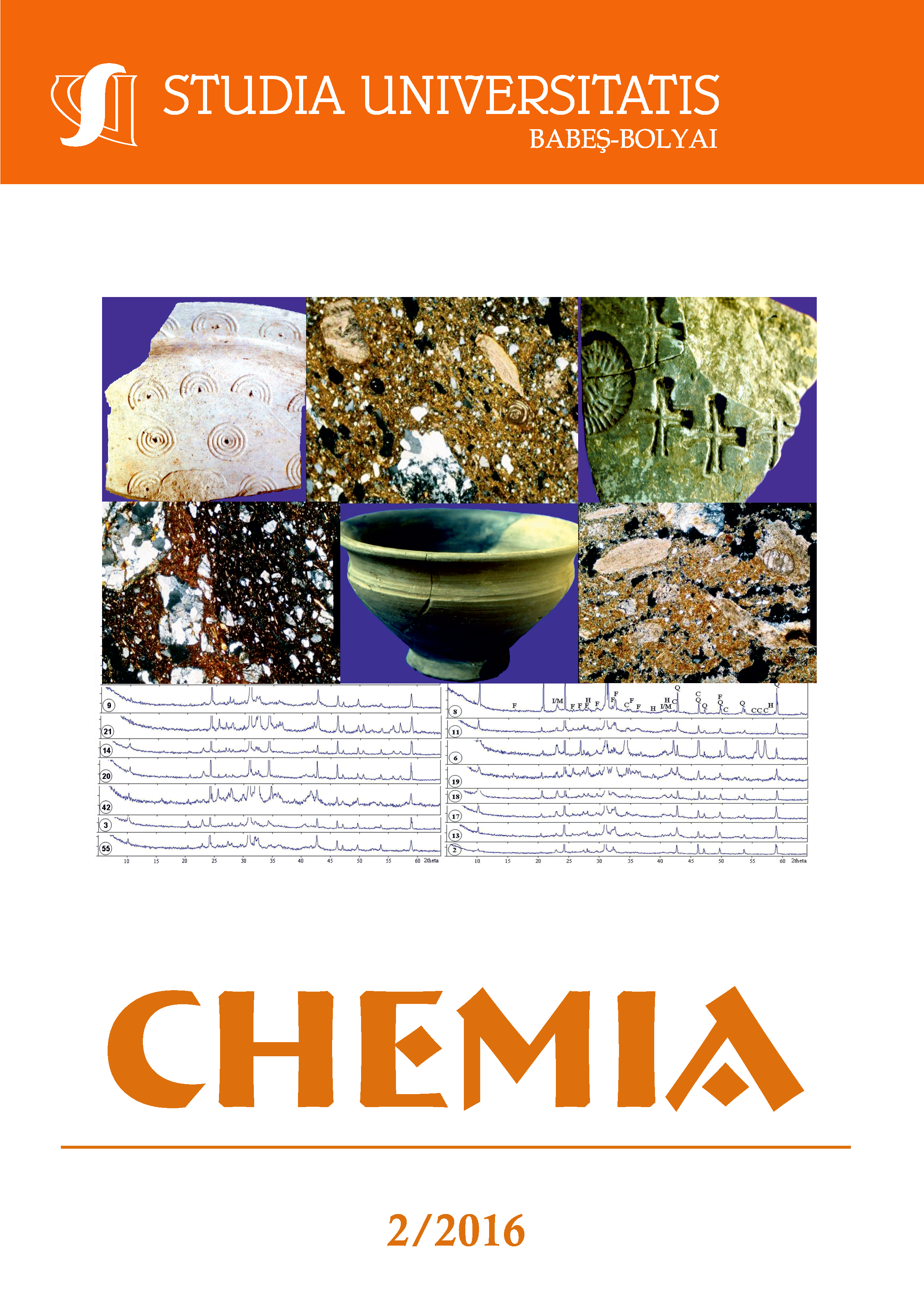

CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF SUCEAG POTTERY, CLUJ COUNTY, ROMANIA

Keywords:

ancient pottery, mineralogical and physical analysis, Suceag archaeological site, RomaniaAbstract

The site at Suceag, Cluj county, Romania, is composed of three different overlapping settlements, each having its own chronology: the first one is dated during the time of the Roman province of Dacia, the second one dated between the second half of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century AD and the last one broadly dated during the 7th-8th century AD. Because of this particular situation, our first attempt was to determine whether some direct connections between them truly existed. The petrographic analysis performed on a series of 56 samples coming from different types of pottery established after analysing all the ceramic material coming from the settlement at Suceag (cca. 4500 pottery fragments) showed that in this case we are only dealing with local products. The colour of the analysed potsherds vary from grey to black indicating reducing atmosphere (25 samples), from reddish-brown to yellowish-brown (24 samples) suggesting an oxidizing atmosphere during firing and 7 samples have a sandwich-type structure probably an incomplete thermal treatment. The matrix is relatively uniform, with clasts of various sizes (up to 3-4 mm). Macroscopically, quartz grains, micas, and ceramoclast could be observed. According to the microscopic grain size, two types of ceramics can be separated: semifine (lutitic-siltic-arenitic), and coarse (lutitic-arenitic-siltic). Based on the ratio between crystalline vs. amorphous phases, microcrystalline, and microcrystalline-amorphous fabrics were identified. As temper, crystalloclasts (quartz, micas, iron oxi-hydroxides, feldspars, amphibole, garnets, epidote, zircon), lithoclasts (quartzite, micaschist, gneiss, limestones), and ceramoclasts were identified. The observed bioclasts are represented by algae, and foraminifera remnants. The porosity consists of both primary, and secondary pores. The pore size vary from 0.5 x 1.5 mm to1.5 x 2.0 mm. Open porosity determined by water absorption capacity vary between 9.09 % - 23.10 %. The X-Ray diffraction analyses confirm the microscopic observations. According to the macroscopic aspects, microscopic features, and physical characteristics, the firing temperature of the studied ceramic fragments is estimated to be between 800-900°C.

References

S. Cociş, A. Paki, ActaMN, 1989-1993, 26-30, I/2, 477.

C.H. Oprean, S. Cociş, Cercetările arheologice de la Suceagu (1991-1992). In: Situri arheologice cercetate în perioada 1983-1992, Bucureşti, 1996, 251, 109.

C.H. Oprean, Ephemeris Napocensis, 1992, 2, 159.

C.H. Oprean, S. Cociş, CCA, 1994, 62.

C.H. Oprean, Eine spätrömische Riemenzunge aus der Siedlung von Suceag (Kreis Cluj). Beiträge zur Chronologie der Völkerwanderungszeit in Siebenbürgen. In: C. Cosma, D. Tamba, A. Rustoiu (Eds.), „Studia archaeologica et historica Nicolao Gudea dicata. Omagiu profesorului Nicolae Gudea la 60 de ani“, Zalău, 2001, 467-478.

C.H. Oprean, Transilvania la sfârşitul antichităţii şi în perioada migraţiilor. Schiţă de istorie culturală, Ed. Nereamia Napocae, Cluj-Napoca, 2003, 137-146.

C.H. Oprean, S. Cociş, CCA, 1996, 116.

C.H. Oprean, S. Cociş, Die Töpferwerkstätten aus dem 5. Jh. n. Ch. aus der Siedlung von Suceag (Kr. Cluj). In: A. Rustoiu & A. Ursuţiu, „Interregionale und kulturelle Beziehungen im Karpatenraum (2. Jht. v. Chr. – 1. Jhr. n. Chr.)“, Cluj-Napoca, 2002, 267-295.

C.H. Oprean, V.-A. Lăzărescu, Ephemeris Napocensis, 2013, 23, 339.

S. Scarcella (Ed.), Archaeological Ceramics: A Review of Current Research, Oxford, 2011, BAR S2193.

W.Y. Adams, E.W. Adams, Archaeological typology and practical reality. A dialectal approach to artefact classification and sorting, Cambridge, 1991, 427.

L.S. Klejn, Archaeological typology, Oxford, 1982, BAR153.

V.-A. Lăzărescu, V. Mom, Pottery Studies of the 4th-Century Necropolis at Bârlad-Valea Seacă, Romania. In: S. Campana, R. Scopigno, G. Carpentiero, M. Cirillo (Eds.), The 43rd Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology: Keep the Revolution Going (CAA 2015), Oxford, 2016, 875-888.

D.E. Arnold, Ceramic theory and social process, Cambridge, 1985.

M.S. Tite, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 1999, 6(3), 181.

M.S. Tite, Archaeometry, 2008, 50(2), 216.

R. Gindele, Ein im Römerzeitlichen Töpferzentrum von Medieşu Aurit‑Şuculeu Entdeckter Römischer Militärischer Beschlag. In: R. Madyda-Legutko & J. Rodzińska-Nowak, “Honoratissimum assensus genus est armis laudare. Studia dedykowane Profesorowi Piotrowi Kaczanowskiemu z okazji siedemdziesiątej rocznicy urodzin”, Krakow, 2014, 337-343.

C. Ionescu, L. Ghergari, O. Ţentea, Cercetări arheologice, 2006, XIII, 387.

C. Ionescu, L. Ghergari, Caracteristici mineralogice şi petrografice ale ceramicii romane din Napoca. In: V. Rusu-Bolindeţ, “Ceramica romană de la Napoca. Contribuţii la studiul ceramicii din Dacia romană,” Bibliotheca Musei Napocensis, XXV, Ed. Mega, Cluj-Napoca, 2007, 434-462.

M. Benea, M. Gorea, Rom. J. Materials, 2007, 37(3), 219.

M. Benea, M. Gorea, N. Har, Rom. J. Materials, 2010, 40(3), 228.

M. Benea, R. Ienciu, V. Rusu-Bolindeţ, Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai, Chemia, 2013, LVIII (4), 147.

M. Benea, V. Diaconu, Gh. Dumitroaia (2015), Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai, Chemia, 2015, LX (1), 89.

C. Ionescu, L. Ghergari, Cercetări arheologice, 2006, XIII, 433.

C. Orton, P. Tyers, A. Vince, Pottery in Archaeology, Cambridge, 1993.

P.M. Rice, Pottery Analysis. A Sourcebook, Chicago-London, 1987.

A.O. Shepard, Ceramics for the Archaeologist, Washington D.C., 1976.

N. Cuomo di Capri, La ceramica in archeologia, Roma, 1985.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2016 Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai Chemia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.